The China connection of five great American family fortunes

The fortunes of some of America’s greatest families that today generously support the best of worthy causes, began in unworthy ways in faraway lands more than 200 years ago.

In those times, Britain and the new United States of America were flexing their muscles on the world stage when opium suddenly became a major commodity. It drugged China, mocked their government, made Britain rich and enticed American merchant barons to join the action.

In China, the Qing Emperor’s government outlawed opium but they couldn’t stop the Americans and Europeans from exploiting the illicit trade.

Opium use was not illegal in America however and soon came to the American West and spread across the land.

The early American China traders included the names of Astor, Forbes, Russell, Delano and Perkins — all of them trading in opium.

Opium (Papaver somniferum) comes from dried latex of opium poppy flowers, found worldwide and was used in ancient times as a painkiller and for treating dysentery and cholera.

Orchestrated by the East India Company, the British were buying huge quantities of Chinese goods to sell in the U.K. and Europe, and the Chinese demanded to be paid in silver or gold and weren’t interested in buying most foreign goods to balance the trade.

By taking over the opium-growing business in India, the British sold the drug in China where it was in high demand — even though outlawed. The proceeds from the illicit trade paid for the silver and gold.

Once involved, the American merchant barons sold the Chinese both Turkish and Indian opium.

John Jacob Astor, who was a fur trader who founded Astoria, Ore., was the first American to make a fortune with opium, starting in 1816, but to his credit quit the opium business three years later to become even wealthier pursuing other avenues.

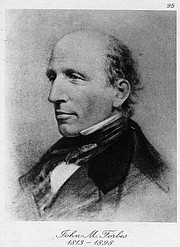

John Murray Forbes was an American railroad baron, merchant, philanthropist and abolitionist from Massachusetts, who as a young man was sent to China along with his sea captain brother, Robert Bennet Forbes, by Boston traders Perkins and Co. to build the company’s China trade.

In 1838, Forbes founded today’s giant J.M. Forbes & Co. investment firm that successfully built its China trade through the two Opium Wars — 1839 to 1842, and 1856 to 1860 — “amassing a large fortune,” along the way.

Though the Forbes Co. website discusses its corporate history in detail, there’s no mention of opium. Other sources however state that the Forbes family was indeed involved with opium in what’s called the Old China Trade (1783-1844), a period marking the start of major trade between the U.S. and China.

Another American baron was Samuel Wadsworth Russell, who arrived in Canton, China, in 1819 as a trader for Edward Carrington & Co., dealing in many products — including opium — and making enough money to start his own Russell & Company, trading mostly in silk, tea and opium.

By 1842, it was the largest American trading house in China until it closed in 1891.

Russell’s Greek Revival architecture mansion in Middleton, Conn., is now a National Historic Landmark.

President FDR’s maternal grandfather, Warren Delano, Jr., also went to China, hired by Russell & Co. to head its operations in Hong Kong, Macao and Canton.

By age 33, he was a wealthy man who in the following years bounced between the U.S. and China and weathered through the Opium Wars.

Then tough economic times during the Panic of 1857 cost him his fortune, but the Civil War saved him and made him rich again when he sold opium to the U.S. War Department “to ease the pain of the wounded and dying.”

Col. Thomas Handasyd Perkins was another Boston merchant whose vast wealth was built on misery. He started as a slave trader in Haiti, and then took Northwest American furs to China where he became a major smuggler of Turkish opium.

It didn’t take long for the opium to wreak havoc throughout Chinese society; that didn’t begin to end until Mao’s Communists took over after World War II.

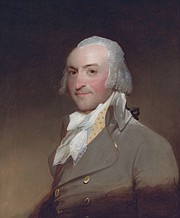

One American in the China trade who did not deal in opium was George Washington’s good friend and prosperous Boston merchant Robert Morris.

It was Morris who saved Washington’s struggling army during the darkest days of the American Revolution.

Putting his personal financial credit and reputation on the line, he raised $10,000 that Washington badly needed to keep the troops together, cross the Delaware and defeat the British at the Battle of Trenton on Dec. 26, 1776.

Opium came to America about the time of the first wave of Chinese immigrants around 1815. But the big wave took place after gold was discovered in California and the railroad tracks began opening the nation.

Cheap Chinese labor helped do the work, and was welcomed by business interests — but not by the American public or labor unions who didn’t understand them or their culture.

In entry ports like San Francisco, Chinatowns developed and opium dens flourished — spreading inland as the Chinese followed a variety of job opportunities — including even working the plantation fields of the South after the Civil War.

Opium was legal in most of the U.S. and Canada until 1908, and never caused a problem like today’s drug culture. Most users in those days were Chinese — the opium helping them ease the burdens of exhausting work and rabid discrimination by white America and the U.S. government.

Then whites who already were using opium for medicinal purposes also started smoking it.

Chinese emigrants to cities such as San Francisco, London, and New York brought opium smoking and opium den traditions with them that were soon commonplace throughout the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere in America.

Boise was said to have the largest Chinatown outside San Francisco.

Raw opium was traditionally and legally refined by Chinese, but in the late 1800s when the U.S. government restricted opium refining to American citizens only, the Chinese moved their refineries to Canada, with about two dozen in Victoria, British Columbia, alone. For nearly 50 years Victoria was the largest opium refining center outside Asia.

Most of those B.C. refineries diversified by also importing Chinese textiles, tea and other goods, as well as arranging contracts for Chinese laborers.

The U.S. Customs Service was another player in the opium business — chasing smugglers and collecting import duties.

But two enterprising smugglers hit the jackpot in Puget Sound:

For years, opium smugglers quickly dumped their illicit cargo overboard when Customs boats hove into view. The opium was packed in tins that were really made of brass and sealed with solder — surviving the salt water.

A 1907 story in “The Coast” magazine told an interesting tale attributed to an unnamed retired smuggler who developed his own underwater gear and then played cat-and-mouse with the Customs agents:

“I had a rubber breathing apparatus fitting over my head. A tube led up to the surface of the water and bobbing around among a lot of seaweed or rushes on a shallow bay. It was hard to discover which was the rubber breathing tube and which the innocuous seaweed.”

On one dive, by chance he stumbled across an “underwater El Dorado” — a dumping ground for abandoned containers of opium.

“The sea floor was literally paved with the precious little cans.”

With a trusted friend, they posed as “wealthy young house-boating tourists” fishing from a luxurious houseboat, well stocked with fishing gear, cigars and whiskey, and anchored over the treasure below.

At night they dived for their canned opium, filling their boat again and again for five years.

Whenever revenue agents came aboard to investigate, they “sampled our good cigars and laughed at our jokes, and each succeeding summer they joyously welcomed us and our hospitable house boat to those remote and loggy wilds… The story ended with, “We worked out all the big deposits by the end of the fifth summer…As we had by this time a million dollars apiece in the Elliott Bay National bank, we sold the luxurious houseboat and returned to the paths of financial rectitude.”

Somewhere on the ocean floor in the chilly waters near Seattle, there may be more valuable containers awaiting discovery by some enterprising scuba divers — or alert drug enforcement agents.

Who’ll find it first?

•••

Syd Albright is a writer and journalist living in Post Falls. Contact him at silverflix@roadrunner.com.