Prosecutor holds JRI to the fire

One would believe that a man with an extensive criminal history that includes being found guilty of escaping from jail would be looking at some serious prison time.

This is not that case though with 50-year old Roy Bieluch of Kellogg, Idaho, and Shoshone County Prosecuting Attorney Keisha Oxendine believes that Idaho’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) is the reason.

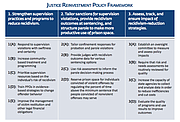

According to the Justice Reinvestment in Idaho Report, located on the Idaho Department of Corrections (IDOC) website, the JRI was employed in Idaho after a study conducted by the Council of State Governments Justice Center (CSG Justice Center) found that there were several issues with Idaho’s prison system that needed to be addressed.

Signed into law by Idaho Gov. Butch Otter on March 19, 2014, the JRI was instituted to fix three main problems or “challenges” that the study found to be present.

The first challenge — address what the report refers to as “a revolving door.”

Explaining this concept, the report states that “the state’s supervision and diversion programs are not reducing recidivism (the tendency of a convicted criminal to reoffend).”

The second challenge- address an inefficient use of prison space to curve prison overpopulation.

“The majority of the prison population comprises people whose community supervision was revoked, people sentenced to a ‘Rider,’ and people convicted of a nonviolent crime who are eligible for parole but have not yet been released,” the report states.

The third challenge- insufficient oversight when it comes to gathering prison related data.

“Idaho lacks a system to track outcomes, measure quality, and assure reliability of recidivism-reduction strategies, so policymakers are unsure whether their investments are yielding intended outcomes.”

The detailed 26- page document details out how the JRI will solve these issues with three multi-step processes, one for each challenge.

Although Oxendine admits that the initial goal of JRI is noble and some aspects of it are useful, the actual implementation of it is causing more problems than it is fixing.

“There are parts of Justice Reinvestment that are good,” Oxendine said, “they implemented certain risk assessment tools and things like that to sort of help evaluate on the front end people’s level of risk, and they are trying to implement different levels of supervision when they are out on probation or parole so that the levels of supervision are meeting the needs of the offender.”

But this is where Oxendine believes the positives end.

“What was lacking really in the big picture of that assessment of the prison population was that the entire criminal history of offenders serving a prison sentence was not considered. The assessment appeared to only look at what charge they were presently serving time on, not their prior criminal history or their probation revocation history. Therefore, at first glance, it appeared all these people in prison were serving time for non-violent offenses such as property crimes or drug crimes, but it did not consider any violent crimes in their past or evidence of potential for violence.”

In an effort to cut down on the prison population in Idaho, Oxendine believes that the JRI in practice has redefined what qualifies as a violent offender, hence criminals who are genuinely threats to society are being paroled out.

“Essentially what has happened is because of this big push and this implementation of Justice Reinvestment, the parole commissions are really sort of forced to start paroling people.”

When brought before the parole commissions at the department of correction level, inmates are supposed to be granted or denied parole based on whether or not they are violent, if they are at high risk to reoffend or not, and if they are a danger to the public.

According to Idaho Administrative code regarding Rules of the Commission of Pardons and Parole — one of the many factors that is to be considered in determining their worthiness for meeting parole criteria is the “prior criminal history of the offender.”

From Oxendine’s perspective, this is not being done successfully in practice.

She sees that the re-offenders who have been released from prison and that have benefited from JRI did so because they were judged solely on what crime landed them in prison; not a complete look of their entire criminal history or their history of probation and what actually led to their prison sentence being imposed.

Referring to repeat offenders who have continually violated the terms of their parole, Oxendine explains, “from a prosecutor perspective, before Justice Reinvestment and even after, it’s not an easy task to get someone sentenced to prison. Essentially you have to show, especially in those cases where we have our repeat offenders, if they’re not sitting there on a violent crime with a victim giving a statement in court, we usually have to show that they have a history of non-compliance with probation.”

Simply put, a prosecutor must show that all other avenues of rehabilitation and all possible remedies to their criminal behavior in the community have been exhausted, proving that prison is the only solution to protect innocents.

Enter, Roy Bieluch.

Bieluch has received a significant amount of attention over the last two years for his attempts to escape incarceration and flee law enforcement officials.

In February of 2015, he made national headlines when he broke out of the Shoshone County Jail in Wallace by crawling through the ceiling and ending up in a locked janitor’s closet.

When cleaning staff unlocked the door, he ran into the main lobby and out the front door.

A massive multi-agency manhunt followed the jail break.

Law enforcement combed through the city of Wallace and the surrounding areas looking for the escaped convict.

Police finally caught up to him after a local homeowner found Bieluch on his property and shot him in the leg when he refused to stay where he was.

When Bieluch was arrested previous to the jail break in October of 2014 for possession of Methamphetamine with intent to manufacture or deliver (the charge that landed him in the jail he would escape from later on), he also had firearms on his person; something that is also against the law since he was already a convicted felon.

This incident combined with his escape from jail, burglary, obstructing an officer, other drug related charges, and a laundry list of other crimes he has committed in other states (the prosecutor’s office could not release his full criminal history, but local law enforcement officials stress that he has a sordid past), one could say that Bieluch qualifies as a violent offender.

Oxendine says that the State of Idaho, because of JRI, sees it differently.

“When he was sentenced in...August of 2015, our recommendation on the meth charge was the maximum that we could recommend and that was seven year unified sentence,” Oxendine said.

“On the escape, we recommended the maximum on that which was five (years) and we asked that they run consecutive.”

Bieluch was ultimately given a seven year sentence on the meth charge (two years fixed, five indeterminate) and five years indeterminate for escaping the jail.

After serving a year in prison combined with 257 days credit he accumulated while awaiting his sentencing in Shoshone County, Bieluch was granted parole after only serving the minimum two-year fixed portion of his 12- year unified sentence.

Upon his release, Bieluch once again made headlines when he fled from a traffic stop in Smelterville on March 17 and eluded law enforcement for several days.

Bieluch had an outstanding felony warrant for violating the terms of his parole.

He we spotted once again in Smelterville on March 21 by an off-duty Sheriff’s Deputy, spurring another drawn out pursuit where Bieluch evaded law enforcement by running back and forth across Interstate-90, attempting to flag down vehicles in the process.

Though he was eventually taken into custody, it could be argued that this most recent saga with Bieluch could have been completely avoided if he was still in prison.

Oxendine says that an effort led by many of the county prosecutors, law enforcement, department of corrections, and others, in Idaho is currently being made to amend JRI so that situations like this can be prevented in the future.