OP: Time for Shoshone County to Get a Fair Shake From the U.S. Forest Service

A not very optimistic article in the New York Times a few days ago, suggested that America’s rural economies are probably in a death spiral. Something called “agglomeration,” said the author, was killing them. High tech expertises, he wrote, like to co-locate with themselves, thus creating so-called agglomerations of fast-paced, well-paid technology centers in a few selected places around the nation -- and leaving the rest of us essentially to make do with scraps.

Rural places are of course closer to nature – and the natural-resource bases of their economies – than are big cities. Economic enterprises rooted in natural resources, moreover, have become routinely stigmatized in urban metropolises in recent decades. Some of that stigma is deserved of course, but the larger part of it – the part that equates current natural resource practices with the excesses of the remote past -- is not deserved. Damaging consequences have flowed from this stigmatization. One such consequence with hard implications for Shoshone County’s economic wellbeing in particular has been the collapse of timber harvests on our national forest lands since the early 1990s. As public policy scholar Robert H. Nelson pointed out, the U.S. Forest Service’s shift from a “multi-use” philosophy to an anti-forest-management “ecological forestry” philosophy and ethos has wrought devastating consequences for rural communities hosting national forests. Local communities, it may be added, played no role in the Forest Service’s grand philosophical transition.

Just over 70 percent of Shoshone County’s land area is national forest, amounting to about 1.2 million acres. Traditionally, the county received 25 percent of the revenue derived by the Forest Service from timber sales on this land. Ever since the Forest Service’s formative period, early in the twentieth century, these funds have been seen as representing appropriate compensation for the federal ownership and control of national forest lands, ownership that deprived local counties of potential property tax revenue. By the year 2000, however, the collapse in the Forest Service’s commitment to multi-use and logging dramatically reduced these payments. And the federal government had to come up with an alternative method for compensating local counties. Their plan was to gear compensation to a county’s past history, instead of it’s present rate, of federal, 25-percent timber revenue.

It was called the “Secure Rural Schools and Community Self Determination Act of 2000” -- or, more recently, simply “SRS.” Welcome as it was to local timber-revenue-starved county governments and school districts, the act harbored the message that it was an interim measure only. Forested counties, in Congress’s view, were expected to wean themselves away from federal timber payments and “diversify” their local economies with this interim funding. The funding itself declined year after year as part of this imagined weaning process. Some measure of the historical importance of federal timber revenues to local government and county schools can be gained from the scale of these annual SRS payments. Between 2001 and 2015, for instance, Shoshone County received just under $53,000,000 in SRS payments, averaging about $3,500,000 each year. That averages out to almost $300 per capita of the county’s resident population per year.

But although SRS payments thus underwrote county and educational services -- thus also, somewhat lightening the burden of local property tax levels -- such payments did little to replace the real incomes, and their beneficial economic ripple effects, once derived from a vigorous logging industry. SRS also did little to encourage active forest management, which in turn contributed to the massive accumulation of fuel loads in our national forests. New waves of catastrophic wildfire were, and remain, the dire and fearsome threat posed by the latter – a consequence that has made itself painfully evident in the growth in wildfire in the U.S. over the past decade or two.

And now comes news that Idaho’s state government has signed a pact with the U.S. Department of Agriculture that will, it is hoped, turn the corner on forest management and logging on national forests in our state. Enhanced use of “Partnership” and “Good Neighbor” provisions in the federal government’s land management toolkit will allow the state’s personnel and resources to augment Forest Service assets in tackling the sorry condition of too much of our national forest acreage. Only insiders of course will know the reasons for this shift of position. I’m guessing that three factors played significant roles: (1) California’s devastating wildfire experience only weeks ago, (2) the Trump administration’s contrarian attitude toward the balance between economic activity and environmentalist regulation, and (3) the waxing federal expenditure deficit, a factor that makes the Forest Service’s skyrocketing annual firefighting costs all the more noisome and the prospect of federal revenue from national forests all the more attractive.

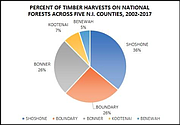

But, and whatever the sources of the change, it now falls to our county commissioners, our school district superintendents, and the rest of us to try to make the most of the opportunity represented by this shift in federal policy. Shoshone County has had a history of being shortchanged by the Forest Service when it comes to forest management projects and timber sales. In March, 2017, former Mullan School District superintendent Robin Stanley published an op-ed in the Coeur d’Alene Press arguing that Shoshone County merited a fulltime Ranger and a fully operational Ranger District office. Almost half of the Panhandle National Forests land area falls in Shoshone County, he pointed out; the other half falling across Kootenai, Benewah, Bonner, and Boundary counties. Yet all five of the Panhandle’s full-fledged Ranger District offices lay outside Shoshone County in the other four counties. So far as I am aware, Stanley’s well-argued op-ed has to date not generated any tangible effort on the part of the Forest Supervisor’s office in Coeur d’Alene to right this imbalance. (I’ll be happy to be corrected on this if I’m mistaken.)

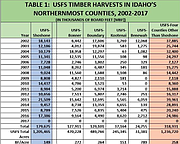

The Forest Service’s record of timber harvests and sales in Idaho’s five northernmost counties echoes the same sort of shortchanging. TABLE 1, above, compares the Forest Service’s history of timber harvests in Shoshone County and northern Idaho’s four other counties from 2002-2017. Shoshone County’s total timber harvest across this period summed to 179,675,000 board feet, or an average of 149 board feet for each of the county’s 1,205,465 acres of national forest area. The four other counties, on the other hand, showed a total timber harvest of 318,931,000 board feet, or an average of 258 board feet for each of this combine area’s 1,236,720 acres of national forest. That’s a 73 percent greater productivity rate in our fellow northern Idaho counties – even though, to repeat myself, Shoshone County’s national forest area is nearly equal to the areas of the other four counties combined. Looked at in another way, Boundary and Bonner counties share over half of recent history’s timber harvest whereas Shoshone County’s share amounted to little more than one-third of the total.

This new federal-state pact signed earlier this month between the State of Idaho and the U.S. Department of Agriculture is titled the “Shared Stewardship Agreement,” and it promises to bring additional state resources and assets to the important task of managing national forest lands. There are good reasons why Shoshone County should go to the front of the line for new projects made possible by the agreement’s signing. For one, our county was the worst hit by the Big Burn in 1910, one indicator of its vulnerability to catastrophic wildfire. For another, the fuel loads in the forests surrounding our communities today are estimated to be two to three times as great as they were in the early days of August, 1910 before the Great 1910 Fire struck. For a third, the disastrous Camp Fire down in Northern California amply demonstrated that modern firefighting technology and manpower are still no match for a raging wildfire nourished by strong winds. I, for one, will not mind at all if the U.S. Forest Service and the State of Idaho play catch-up with respect to their forest management and fire-risk minimization responsibilities to Shoshone County with the new resources granted them by this new federal-state agreement. Like I said, Shoshone County has a verifiably just claim to be at the front of the line.