Ruby Ridge, looking back 30 years on

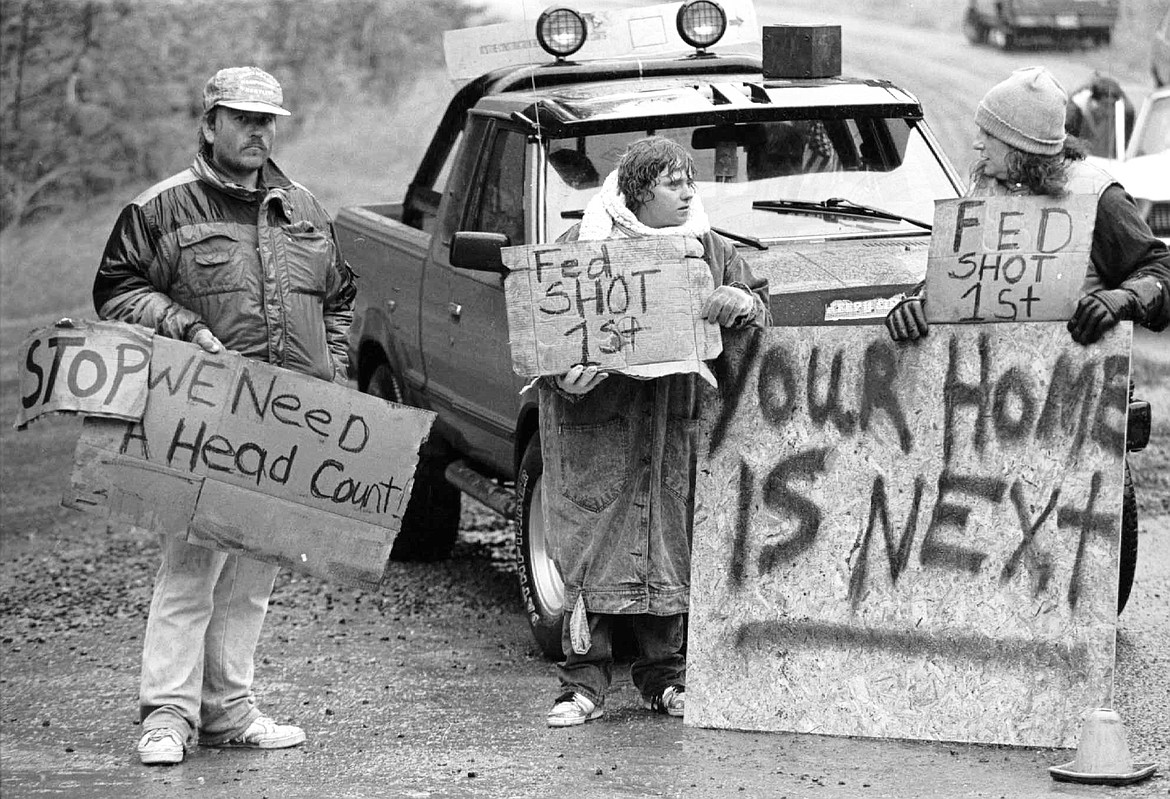

NAPLES — Today marks 30 years since an 11-day standoff shook many in the region to their core.

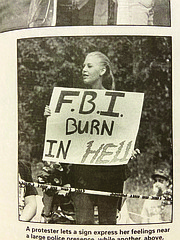

In an effort to execute a bench warrant, federal forces lost an agent and a family lost a 14-year-old son and a mother. The standoff would go on to inspire a generation of anti-government attitudes and organizations.

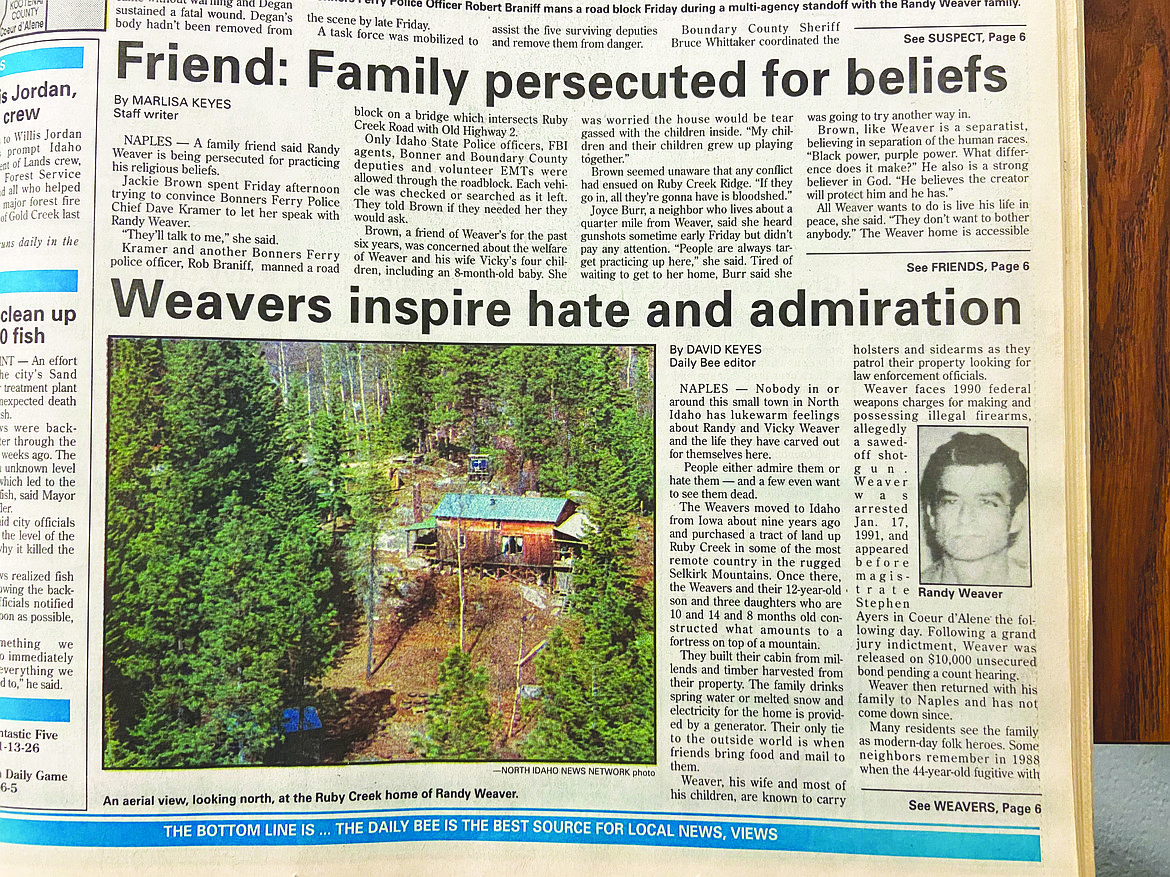

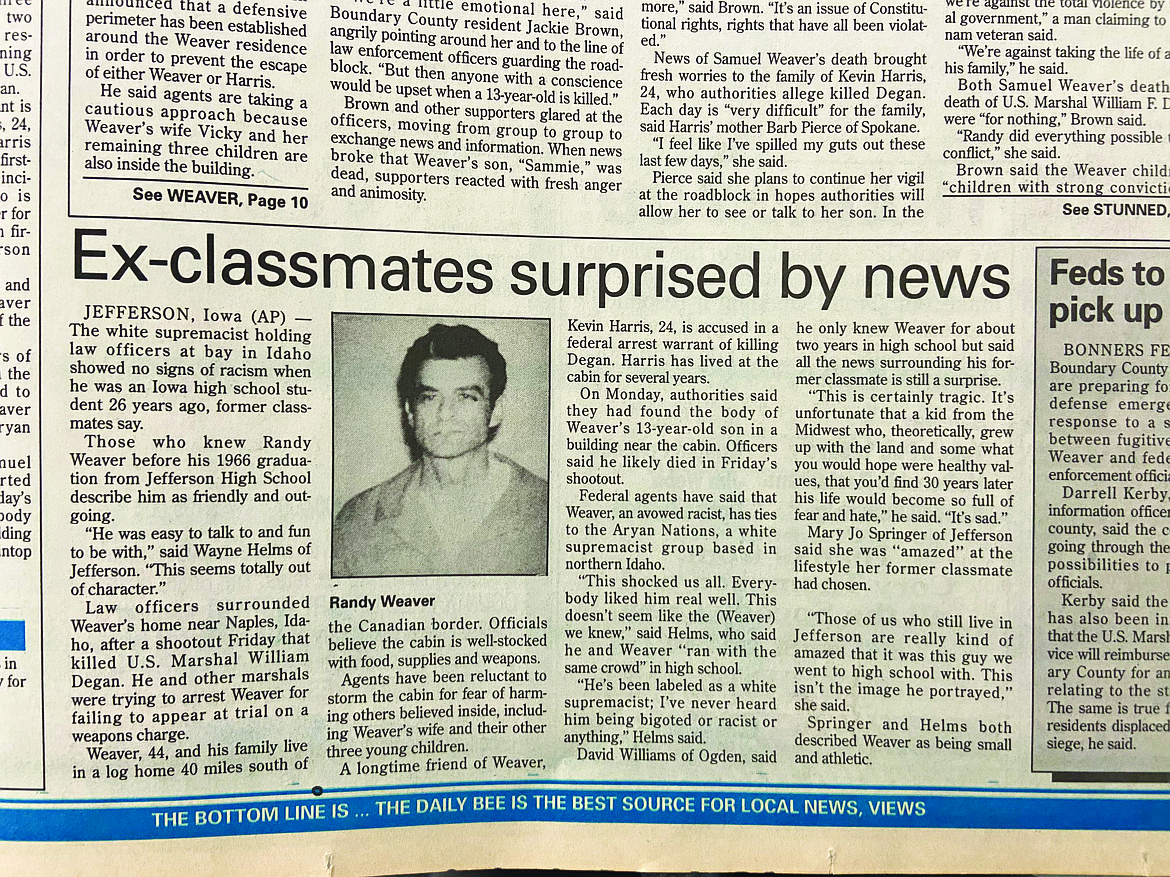

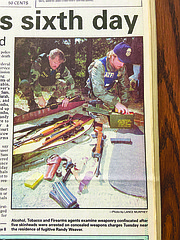

In 1989, Randy Weaver allegedly sold an ATF agent two-sawed off shotguns, purportedly shorter than the federal limit. The agent wanted Weaver to infiltrate the Aryan Nations and serve as an informant. Weaver, while not a member of the group, had attended several meetings and practiced a version of Christianity that claimed white, European-descended peoples as the real tribes of Israel.

Weaver refused. He had moved his family from Iowa to Idaho to pursue a survivalist lifestyle, out of the grasp of what they felt was a corrupt and decadent civilization. The feds had other plans.

According to a 1994 Department of Justice report, Weaver was issued a warrant for a weapons charge in 1990, with a court date of Feb. 19, 1991. When the date was changed to Feb. 20, a probation officer notified Weaver by letter, but mistakenly told him to appear in court on March 20.

This bureaucratic miscue helped set in motion the 11-day, fatal standoff.

According to the 1994 DOJ report, after Weaver failed to appear for trial on Feb. 20, 1991, a bench warrant was issued for his arrest and he was subsequently indicted by a federal grand jury for failing to appear. Another bench warrant was issued.

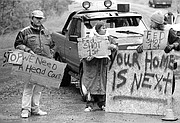

The response to the warrant was signed by the entire Weaver family.

“We, the Weaver family, have been shown by our Savior and King, Yahshua the Messiah of Saxon Israel, that we are to stay separated on this mountain and not leave. We will obey our lawgiver and King,” the letter said. “Whether we live or whether we die, we will not obey your lawless government.”

The DOJ reported that after receiving the letter “it was their conclusion that Weaver never intended to appear for trial on Feb. 19 or 20, nor would he appear for trial on March 20.”

On March 18, the U.S. Marshals Service Special Operations Group got involved.

The U.S. Marshals Special Operations Group reported later that summer that

Weaver was “extremely dangerous and suicidal” and that he had “been preparing for five months for his war or confrontation with law enforcement and it is very likely that he has established numerous fortifications and defensive positions on his property.”

Attempts to arrest Weaver failed, and in October 1991 negotiations for his surrender were attempted through a friend of the Weavers, but also failed.

“The U.S. government lied to me — why should I believe anything its servants have to say,” Randy Weaver said in response. “...This situation was set up by a lying government informant whom your lawless courts will honor. Your lawless One World Beast courts are doomed.

“I have appealed to Yahweh's court of Supreme Justice. We will stay here separated from you and your lawless evil in obedience to Yahshua the Messiah.”

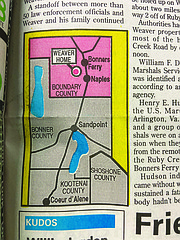

Over the winter, U.S. Marshals monitored Weaver’s residence and strategies for dealing with intruders. They determined he had a 100-yard perimeter around his cabin with 360-degree, high ground coverage. Weaver or his friend Kevin Harris would cover any intruders from a distance until they were identified, either by Weaver’s son Sammy or by Harris. The marshal noted that “Weaver also has a very aggressive dog that will warn them if someone is approaching.”

Marshals continued their surveillance of Weaver and his property, while considering possible apprehension strategies with other federal officials.

On Aug. 21, 1992, U.S. Marshals made another reconnaissance trip to the area.

They parked their vehicle near the Weaver property at about 4:30 a.m. The six marshals split into two three-person teams. One team watched from an observation post around a half-mile from the compound. The other team conducted reconnaissance closer to the residence.

Around 10 a.m. Aug. 21, the recon team approached an outbuilding below the cabin. Marshals thought it could provide a useful counter-sniper point during the planned undercover operation.

It was then the family’s dog started to bark, prompting Harris and the Weavers to stir. The three marshals in the recon team took cover. According to the 1994 report, the marshals hoped the residents of the compound were responding to another vehicle approaching. But then the observation team warned them,”You've got them all coming down the drive."

The recon team ran for cover. They were chased by Harris, Sammy Weaver, and the family’s dog. After dashing through a fern field, the recon team members chose to take up defensive positions in the woods. Marshal William Degan was squatting behind a tree stump when Sammy Weaver and Harris walked in front of him.

Degan jumped up and shouted “Stop! U.S. Marshal.” At that instant, Harris turned around and shot Degan in the chest with a 30.06 rifle. Marshal Larry Cooper, who was also on the recon team and hidden further in the woods than Degan, joined Degan in identifying himself. Upon Harris’ shot, Cooper returned fire with a three-round burst.

After the shots rang out, the family’s dog started approaching the marshals. Marshal Arthur Roderick on the recon team fired a single shot and killed the dog.

And so the standoff began.

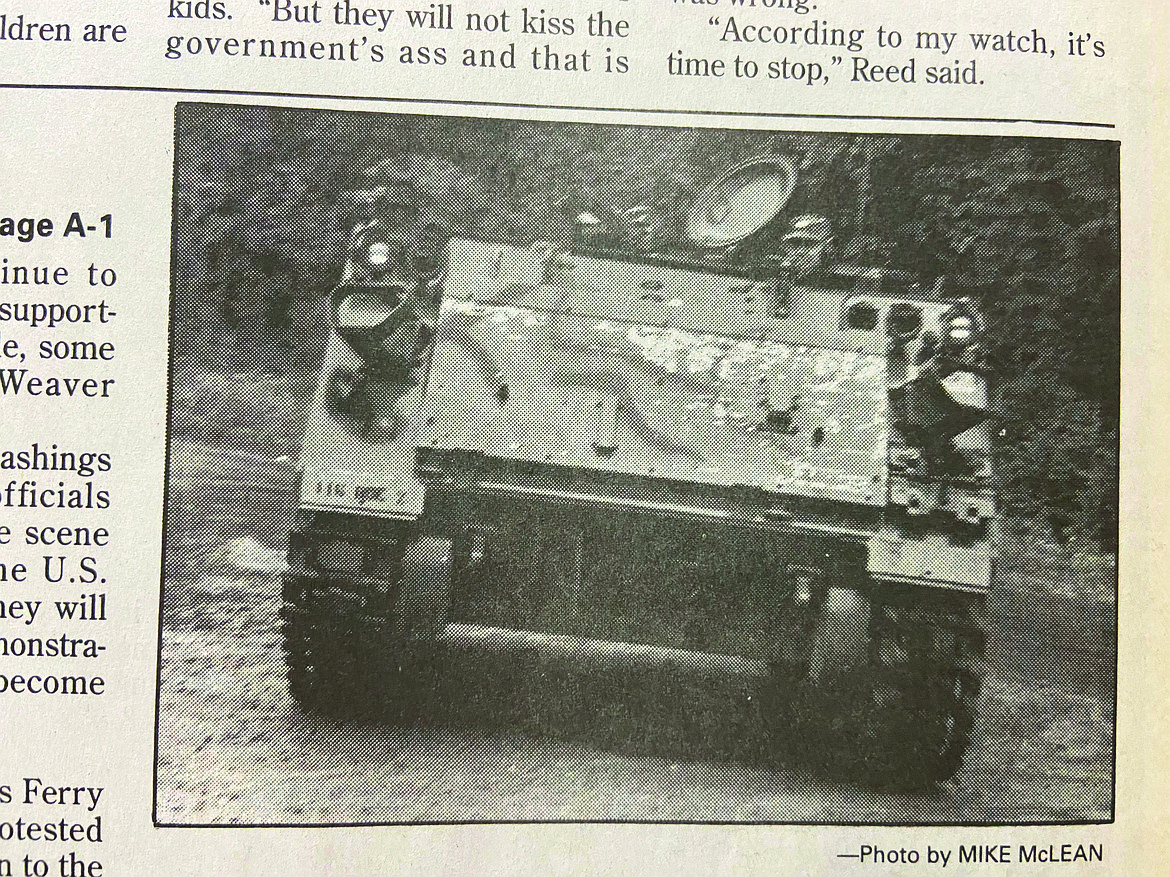

The shooting led the U.S. Marshal Service to contact the FBI, which then activated the Hostage Rescue Team.

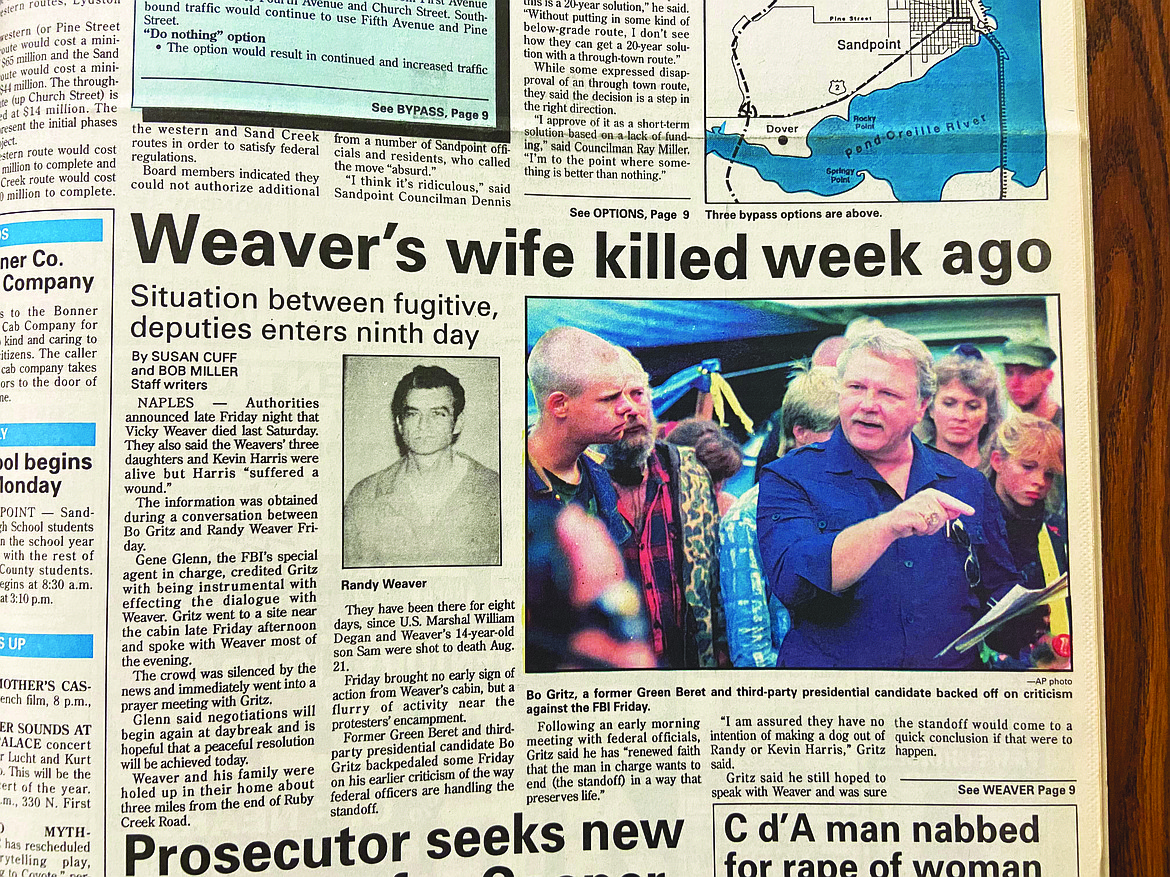

On Aug. 22, the family and Harris were observed leaving the cabin, perhaps to recover the body of Sammy Weaver, who had been shot and killed, although agents had not yet learned of the boy’s death.

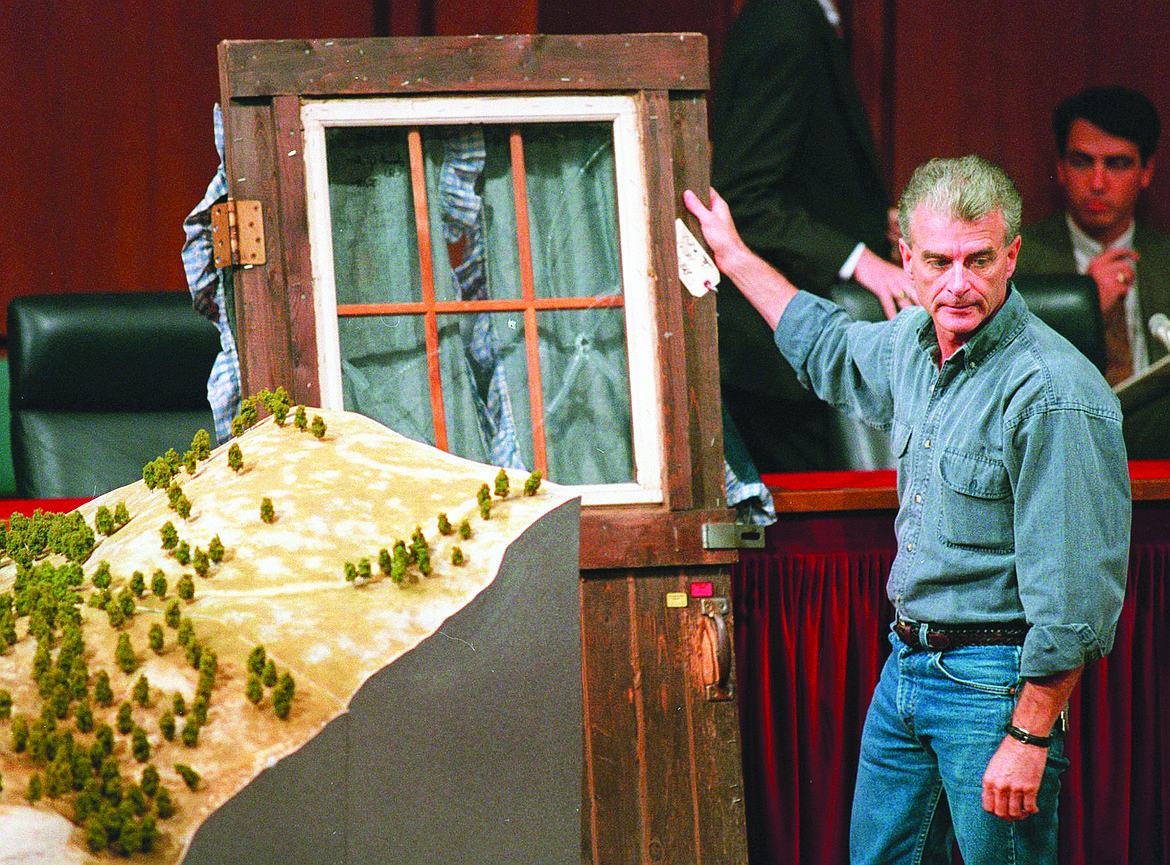

Thinking the Weavers and Harris were going to open fire on an FBI helicopter, FBI sniper Lon Horiuchi shot and wounded Randy Weaver. When Harris made a break for it, Horiuchi fired again. He wounded Harris, but, unbeknownst to Horiuchi at the time, he had also shot and killed Randy’s wife, Vicki Weaver, who was standing at the door of the cabin, holding the door with one hand and her 10-month-old infant with the other.

On Aug. 23 authorities first became aware of Sammy Weaver’s death, during the removal of non-housing structures on the Weaver property. Sammy’s body was found in one of the smaller structures when it was removed.

The DOJ was unable to conclude who initiated the gunfire that day, however they stated in their report that evidence suggests, but does not establish, that the shot that killed 14-year-old Sammy Weaver was fired by Deputy Marshal Cooper.

“Assuming that to be so, we find that there was no intent on the part of Cooper or any of the other marshals to harm Sammy Weaver,” the report said.

The FBI’s role was a key point of concern for the DOJ in 1994. They found the FBI’s rules of engagement for the stand-off “to contain serious constitutional infirmities.”

These constitutional lapses, the DOJ wrote, may have led to the Aug. 22 death of Vicki Weaver. These special rules of engagement were withdrawn Aug. 26 and the usual FBI rules of engagement were put in place.

These rules “were also a departure from the FBI's standard policy on the use of deadly force,” the report said, and their implementation “may have created an atmosphere that caused a hostage rescue team sniper/observer to take a shot that he otherwise would not have taken.”

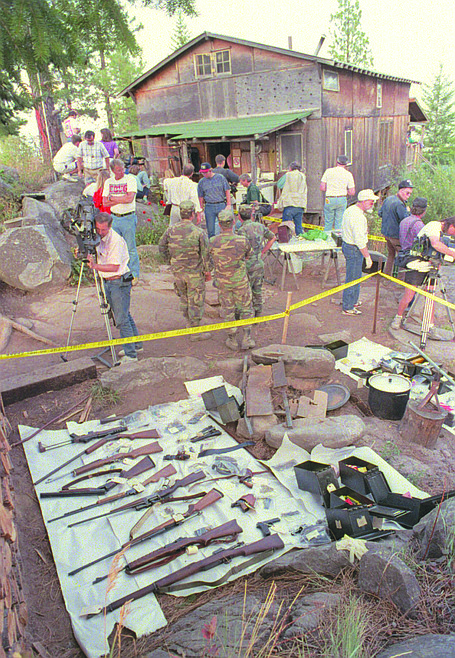

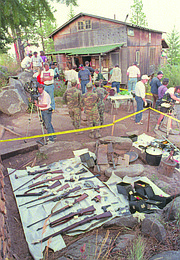

After working through a non-government, third-party negotiator, the surviving Weavers and Harris surrendered on Monday, Aug. 31.

Harris and Randy Weaver were arrested.

According to news reports at the time, one of Randy Weaver’s daughters, Sara Weaver, had crawled around her mother’s body to get food and water for the survivors until the family’s surrender.

Following Randy Weaver’s arrest, Sara and Weaver’s other two daughters were sent to Iowa to live with their mother’s family.

The DOJ report concluded that “The FBI management team favored a tactical strategy and gave insufficient consideration to negotiations as a means to resolve the crisis.

“Negotiation experts at the site were not adequately informed and consulted during the crisis. The failure of onsite supervisors to communicate accurate information to the FBI's behavioral sciences personnel appears to have had a negative impact on attempts to resolve the crisis through negotiation.”

The report noted that the late decision to use third-party, non-government negotiators was a sound one.

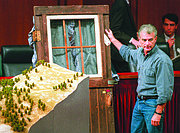

Eventually, Randy Weaver was acquitted of the most serious charges and sentenced to 18 months in prison. Harris was acquitted of all charges.

The surviving members of the Weaver family filed a wrongful death lawsuit. In exchange for dropping their lawsuit, the federal government awarded Randy Weaver a $100,000 settlement and his three daughters $1 million each in 1995.

Harris was awarded a $380,000 settlement to settle a separate lawsuit in 2000.

Weaver died May 11, 2022 from an undisclosed illness, according to a social media post by his daughter Sara.