THE DIRT: Mining in Burke Canyon

The first discovery of lead–silver–zinc ore in the Silver Valley was on May 2nd,1884 in what is now known as the community of Burke. This first discovery was staked and named the Tiger. Three days later, on the opposite side of the Canyon, the Poorman Claim was staked. These early discoveries were just the beginning. Over the next few years, more than seventy additional mining claims were staked along Canyon Creek, making it one of the most prolific mining areas of the Silver Valley.

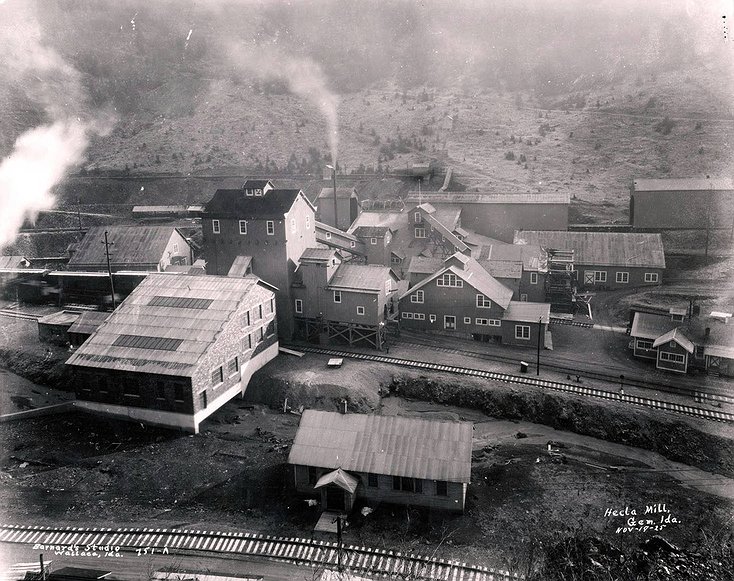

During this era, mining and milling practices were drastically different than those of today and did not directly take into consideration human health or ecological impacts. The early mills constructed to process and concentrate the ores were relatively crude, and the mineral recovery rates were much lower than modern methods. Early mills relied on hand sorting and the use of equipment such as stamp mills, jigs, buddles, and vibrating tables to separate the metal-rich ore from the less valuable materials. These methods were very inefficient, at times recovering less than 75% of the metals from the ore and leaving behind concentrated levels of lead, arsenic, and zinc in the waste, known as tailings. Though the mines knew that technologies would change, and extraction methods would improve, Burke Canyon is extremely narrow, making it nearly impossible to stockpile materials for future processing. Instead, leftover mine tailings and the slimes created by mixing water with the tailings were deposited directly into Canyon Creek, or piled onto hillsides and into gullies allowing gravity and surface water drainage to carry them to the creek. With the rapid growth of Burke Canyon, timber quickly became a precious commodity needed for mine timbers, railroads, mill and home construction, and fuel. The hillsides in and around Canyon Creek were quickly stripped bare, increasing the rate of runoff from the hillsides. This, combined with the large volume of tailings already clogging the creek channel, raised stream levels so that overbank flooding was a common occurrence, further distributing the contaminated materials throughout the canyon.

As time passed and more mills were constructed along Canyon Creek, farmers downstream witnessed changes to their land as mine waste inundated their farms. In 1903, all these factors led to the first lawsuit against a mining company by a Shoshone County farmer living downstream of the pollution sources. The complainant claimed that the mine wastes being deposited onto his land by Canyon Creek were killing crops, hay, and other vegetation, and poisoning his farm animals, some to death. During the trial, the mining company defended itself by citing the Idaho State Constitution which granted preferential water use for mining and milling purposes over those for agricultural use due to the economic benefits of the mining industry. Despite other similar lawsuits filed over the years, area mines were legally allowed to continue directly discharging waste materials into area water bodies until 1968.

Nearly 100 years of historic disposal practices took a toll on much of the Silver Valley and the Lower Coeur d’Alene River Basin region, which led to the area being listed as a federal Superfund Site enabling cleanup actions to be implemented. Early remedial activities to address widespread contamination focused on residential yards, schools, parks, and community areas and much of those cleanup efforts have been completed. Now remediation efforts have turned to the more isolated mine and mill sites, including many found in Burke Canyon. Work to remove contaminated materials in the town of Burke began last year and will continue throughout the gulch. Burke Canyon is a historical gem, and cleanup crews are taking measures to preserve historical structures and features as best as possible. While remedial actions are essential to protect human health, the environment, and our ecology, considerations for preserving our history are also a major consideration in this process.

The Dirt is a series of informative articles focused on all aspects of cleanup efforts associated with the Bunker Hill Superfund Site. Our goal is to promote community awareness of contamination issues, to provide tools for protecting public health, and to keep the community informed of current and future cleanup projects. The Dirt is a group of committed and local experts from multiple agencies including the Basin Environmental Improvement Project Commission, Panhandle Health District, Shoshone County, Silver Valley Economic Development Corporation, and the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality.